The transition to a global circular economy supported by a clear and transparent rules-based trading system is a key solution to address the unfolding triple planetary crisis. The WTO has the potential to be central in this process of regulatory alignment by ensuring a flexible application of common circular economy principles globally and avoiding costly market fragmentation.

This article is part of a Synergies series on reviving multilateralism curated by TESS titled From Vision to Action on Trade and Sustainability at the WTO.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not

necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or

funders.

-----

Extraction and processing of the earth’s material resources are the main drivers of the triple planetary crisis. These activities account for over 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions while the use of biomass alone accounts for over 90% of the total land use-related biodiversity loss and water stress. In addition, the manner in which we consume our resources is largely inefficient as material use has increased more than three times over the last 50 years and is expected to continue increasing by almost 60% by 2060 while material productivity has stagnated and shows no sign of future increase.

The transition from such an inefficient linear production and consumption model to a circular economy would therefore support resource efficiency to reduce environmental impacts, notably in high-income countries which use six times more materials per capita. However, this transition must be based on multilateral collaboration and coordination to prevent the risk of developed economies creating distortions and unnecessary barriers to trade by leveraging their existing comparative advantage(s) and eventually fostering a circularity divide.

Members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) aim to support this transition, notably through ongoing discussions at the Informal Working Group on Circular Economy – Circularity convened under the member-led Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions (TESSD). The informal working group published a mapping of trade measures notified by members to the WTO on circular economy on the occasion of the 13th Ministerial Conference in February 2024. Members are now exchanging on how to take this agenda forward.

The transition to a circular economy must be based on multilateral collaboration and coordination to prevent the risk of fostering a circularity divide.

State of Play of Deployment of Circular Economy Solutions

The TESSD mapping exercise of measures that relate to circular economy finds a total of 520 measures notified between 2009–2021, mostly under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (41% of measures) and the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (35%). The most active members are the United States (22% of measures), followed by China (9%), Korea (6%), and the European Union (4%). Uganda is the only developing country among the top 20 members notifying circular economy-related measures to the WTO with seven measures. Interestingly, the vast majority of measures, both in terms of support and technical regulations, relate to a product's end of life or waste disposal (Figure 1). The number of notified measures directed at upstream activities, such as aiming to reduce or substitute products (and thereby resource use), is substantially lower.

The current focus therefore clearly seems targeted at reducing the environmental impact of end-of-life products rather than addressing the unsustainable use of resources embedded in the upper stages of the life cycle of a product. Upstream measures (i.e. measures aimed at raw material extraction and product design/use) combined only account for 30% of all measures notified, while measures targeting end of cycle and waste disposal represent 54%. These upstream measures, such as extending product lifespans through repair measures, are also concentrated in a limited number of sectors like vehicles and electronics. Meanwhile, the highest number of circular economy-related measures are found in the plastics and packaging sector, of which nearly half are aimed at recycling.

Of course, these findings only cover official notifications to the WTO under specific agreements and are not comprehensive in terms of ongoing initiatives relevant to circular economy globally, especially in developing economies. The mapping exercise undertaken by Chatham House in collaboration with UNIDO currently lists 75 national circular economy “calls to action”, “roadmaps”, and “operational strategies” across the world. These initiatives encompass 2,882 individual actions, thus confirming that circular economy-related policy initiatives are not limited to trade-related measures officially notified to the WTO. The mapping exercise also highlights the dynamism of the European Union in adopting such initiatives, as the proportion of EU roadmaps and strategies amounted to 70% of the total in 2024, thus demonstrating greater activism than the 4% of notified measures at the WTO noted above.

Yet most interestingly, the Chatham House mapping project sheds lights on the current momentum of circular economy initiatives in developing economies, with operational strategies and roadmaps already in place in Nigeria, Rwanda, and Ghana, as well as policies under development in Benin, Cameroon, Chad, and Ethiopia. Such momentum is expected to continue, as over 10 more roadmaps had been announced in Latin America, Africa, and Asia as of May 2024. These initiatives also demonstrate a broader consideration of product life cycles and a stronger focus on upstream action, with initiatives related to circular resources management, for instance, featuring higher than waste management.

The Role of the WTO as a Key Driver of the Transition

As noted, circular economy initiatives are burgeoning around the world, including in developing economies, but with a lack of multilateral coordination and collaboration. The WTO so far appears to somewhat fail to fully monitor these evolutions beyond end-of-life measures and this is jeopardizing its capacity to play its full potential in coordinating the roll out of circular economy measures throughout global value chains. This is particularly important in the current fraught geopolitical context dominated by state policy approaches towards resource security and reshoring or friend-shoring of supply chains, marking the emergence of circular resource nationalism.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the role of trade policy in fostering a global circular economy is relatively well documented and potential solutions are already being brought forward. The role of the WTO is now more essential than ever to support these solutions and prevent, or at least mitigate, the risks of market fragmentation. Core WTO principles for a rules-based world trading system are key. These include the principle of non-discrimination, which ultimately seeks to ensure that resources, goods, and services are available at affordable prices for all actors in cross-border value chains, and that of subsidiarity, by which the WTO focuses on solutions that are relevant at the international level while most decisions should be taken as close as possible to affected people to ensure impact.

The role of trade policy in fostering a global circular economy is relatively well documented and potential solutions are already being brought forward.

Among these solutions, the need to come up with common recognition(s) of what constitutes circular goods or services and move towards regulatory alignment stands out as a priority as this would unlock the potential for market measures both to facilitate circular trade and limit the most socially and environmentally harmful linear value chains.

While respecting WTO compatibility, members could take concrete measures in that direction, such as officially rekindling discussions on definitions and classifications of circular goods and services, but with the stated intention of focusing on mutual recognition aspects in an inclusive manner rather than mere tariff solutions in order to avoid the risk of a breakdown in talks as occurred for the Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA).

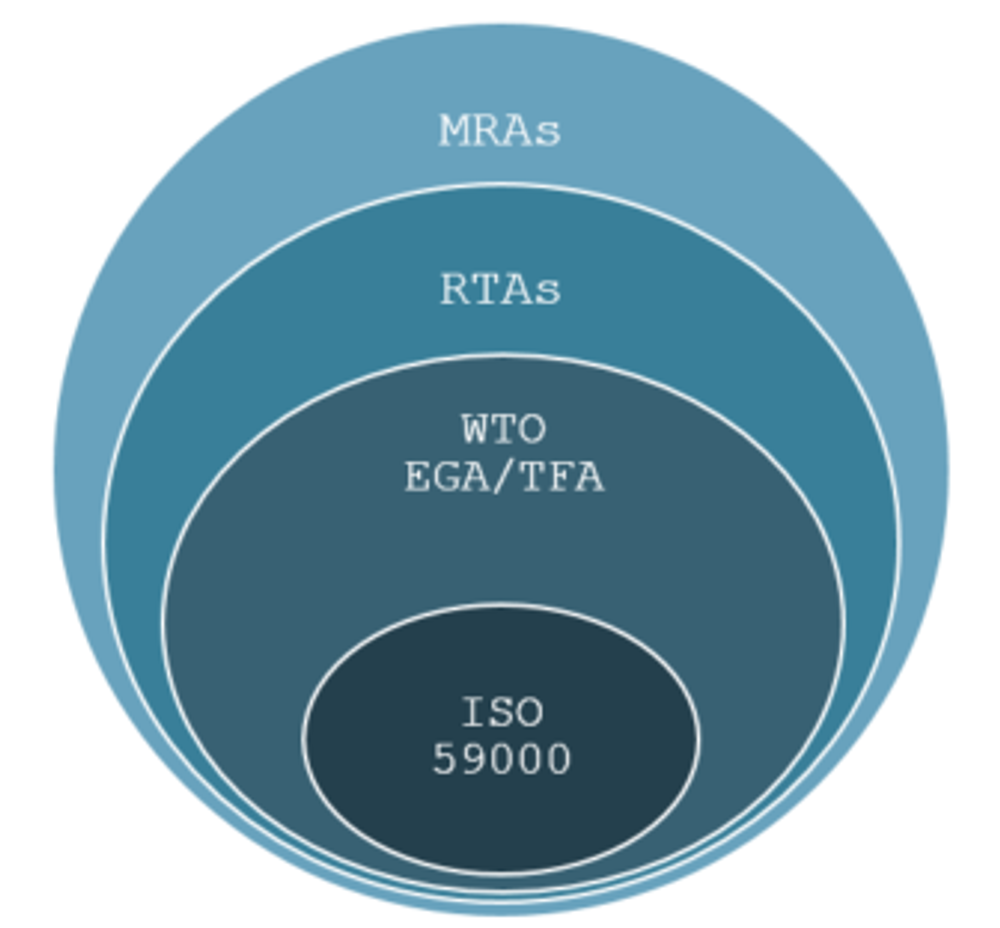

To prevent such deadlock, the notion of concentric circles (illustrated in Figure 3) could be useful when considering circular economy standards to fully account for the various capacities of members to align with these common practices. These concentric circles would include the adoption of mutual recognition agreements (MRAs), the integration of relevant provisions in regional trade agreements (RTAs), a relaunched EGA at the WTO, and, for those members/companies with the capacity to do so, certifications under the recently adopted ISO 59000 series on circular economy.

Figure 3: A Dynamic Alignment System for Circular Economy Solutions

The WTO is arguably an ideal forum to drive such a concerted approach. While negotiation of a fully-fledged EGA would presently appear highly optimistic, there are many provisions in the existing WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) that could be leveraged to promote the concept of trusted trade in reverse supply chains and achieve the same objective of common recognition of circular economy goods and services while supporting customs and market surveillance authorities to embark on the process, especially in developing countries.

Under this approach, countries would be encouraged to integrate their circular economy standards deeper and deeper, thereby further liberating the market potential of circular economy goods and services, yet without presuming any particular level of economic development or domestic capacities. The process could start with a “simple” MRA with trusted partners, eventually moving towards more stringent definitions, with the ISO 59000 series providing the ultimate benchmark for these discussions and cooperation.

This coordination effort would be fuelled by agreements to further improve the Harmonized System (HS) linked to tariff and non-tariff solutions (e.g. subsidies) to promote circular trade over non-circular options. It would also be supported by specific initiatives based on principles of extended producer responsibility (EPR); a key policy approach to improve the price dynamics of circular practices for economic operators. Yet such policies currently tend to focus on downstream activities while remaining largely confined to the domestic level, thereby failing to address properly largely globalized value chains where goods are disposed or recycled at the end of the life cycle in a different country. The WTO could facilitate international cooperation to formulate and promote cross-border EPR schemes that include upstream considerations such as circular design while ensuring that the EPR fees follow the goods across borders. This would help to address the current focus on downstream considerations at the WTO, and support greater transparency and traceability on global material flows throughout the life cycle.

The role of the WTO is now more essential than ever to support these solutions.

Consultation, Coordination, and Financing

In order to be impactful, these renewed efforts at a global transition towards circularity must be concerted and financed, as well as contingent on effective capacity building measures to address the adaptation challenges of vulnerable operators, such as smallholders and micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) in developing economies, to adopt new circular economy practices and standards. Support measures should also include technology access and diffusion agreements as well as digital skills training to drive innovation towards circularity in production processes in developing countries.

These support measures should be embedded and streamlined in all cooperation mechanisms, with major economies and donors such as the EU, United States, China, and multilateral development banks playing a crucial role, thus further highlighting the necessity of coordination among a variety of stakeholders. The role of international cooperation programmes and political alliances such as the Global Alliance on Circular Economy and Resource Efficiency (GACERE) could also be further enhanced.

The transition to a global circular economy supported by a clear and transparent rules-based trading system is a key solution to address the unfolding triple planetary crisis. The WTO has the potential to be central in this process of regulatory alignment by ensuring a flexible application of common circular economy principles globally and avoiding costly market fragmentation. Members now have the responsibility to drive this agenda forward.

-----

Antoine Oger is Research Director, Institute for European Environmental Policy.

Pierre Leturcq is Head of Programme, Global Challenges and SDGs, Institute for European Environmental Policy.

-----

Synergies by TESS is a blog dedicated to promoting inclusive policy dialogue at the intersection of trade, environment, and sustainable development, drawing on perspectives from a range of experts from around the globe. The editor is Fabrice Lehmann.

Disclaimer

Any views and opinions expressed on Synergies are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

License

All of the content on Synergies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

license. This means you are welcome to adapt, copy, and share it on your platforms with attribution to the source and author(s), but not for commercial purposes. You must also share it under the same CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here or if you have any other question related to Synergies, send an email to fabrice.lehmann@graduateinstitute.ch.