The IMO has committed to new and much upgraded climate targets and objectives in its 2023 revised strategy on greenhouse gas reduction. The equity test of this strategy is whether or not the organization and its members can grapple with policymaking to incentivize not just an energy transition, but an equitable energy transition.

This article is part of a Synergies series on climate and trade curated by TESS titled Addressing the Climate Crisis and Supporting Climate-Resilient Development: Where Can the Trading System Contribute? Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

-----

In 2025, multilateralism will face a critical test both on climate but also on equity. The International Maritime Organization (IMO), the specialized UN agency that regulates international shipping, surprised many when in 2023 it committed to new and much upgraded climate targets and objectives in its revised strategy on greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction. These targets (20 striving for 30% reduction in GHG by 2030, 70 striving for 80% GHG reduction by 2040, and net zero GHG around 2050) essentially commit international shipping, the enabler of global trade, to a wholesale transition away from fossil fuel use by the end of the 2030’s.

However, the resolution is a target—the test of multilateralism is whether the IMO and its member governments will create policy strong enough to drive the massive investments needed for new energy supply chains and a new (or at least significantly retrofitted) global fleet of ~50,000 ships. The timeline already committed to in 2023 by the IMO is for the policy measures (a mandate on the fuel/energy used and a GHG pricing mechanism) to be finalized in April 2025 and enter into force in 2027. Good progress in intervening meetings, including most recently in September/October 2024, has been made and there is no reason not to anticipate that timeline coming to fruition.

IMO’s GHG Reduction is Not Just a GHG Mitigation Matter

The IMO is often described as a “technical” agency. Its remit is comparatively simple—to make rules relating to safety and pollution prevention. Its origins come from specifying standards for life-saving equipment, following the sinking of the Titanic. Addressing GHG emissions is not simple—one consequence of regulating GHG is accepting that the IMO is no longer in the comparatively simple territory of its origins but regulating something that impinges on a much broader space that can easily bump into areas also considered (by the same countries) at the UNFCCC, UNEP, UNDP, FAO, UNCTAD, WTO, and other intergovernmental organizations.

Whether envisaged or not, trade and economic development has become a central issue to the IMO’s GHG debates. The origins for this come from the IMO’s initial strategy on GHG emission reduction in 2018, with the guiding principles expressly acknowledge the impingement on other UN areas with “the need to be cognizant of [ … ] the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.” One example of the practical implementation of this “cognizance” at the IMO was the development of a subsequent resolution and procedure for assessing impacts on states arising from GHG regulation, and a commitment to assess and address “disproportionate negative impacts.”

This commitment means that in its process for finalizing the GHG measures, which it is due to adopt in April 2025, the IMO commissioned UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to model the impacts of a range of different policy options on states, looking at imports/exports and GDP. And this is where the critical test—or stark choice—relating to equity (between states) is laid bare. The full study and the executive summary and findings (Section 7.1) are well worth a read—the challenges of modelling which economy wins or loses in 2050 and by how much are far from trivial and the limitations of the results cannot be done justice in this short article. However, in essence, the work shows that the path ahead falls to two different choices on how to incentivize transition, whilst recognizing that it will be a gradual process happening at different speeds in different parts of the world. These two choices in turn play into fundamental differences for future trade and development:

- Fuel-standard-led transition – a trading mechanism in which more polluting ships compensate less polluting lower GHG emitting ships.

- Levy-led transition – a universal price on all GHG emissions, with revenues redistributed to incentivize both the energy transition and an equitable transition (including compensation for the most economically impacted and climate vulnerable countries).

Different Policy Scenarios Have Different Impacts on Trade and GDP

UNCTAD has modelled a range of scenarios and combination of parameters, which cannot easily be summarized. The global average impact on trade and GDP are small, but the relative changes in trade and development between countries are not insignificant.

Variation in the way a country is impacted comes from differences in the nature of their use of international trade (what they trade and who with), and the shipping network that services this trade. The consequence of any decarbonization policy parameter set is to increase transport costs, primarily because the technology transition from cheaper fossil fuels to more expensive renewable energy sources adds costs. UNCTAD estimates the increase in maritime logistics costs (the total costs of moving a good from country A to country B) ranges from 5–19% in 2030 to 78–85% in 2050, depending on the specification of policy parameters. The cost increase is greater and less variable in 2050 because by that year shipping has essentially completely decarbonized and, therefore, is carrying the cost of the full fleet’s transition to zero emissions technology.

The sensitivity of a country’s trade volumes and GDP to that transport cost increase is not the same across countries, and is generally regressive; meaning that the lowest income countries, especially least developed countries (LDCs) but also small island developing states (SIDS), experience the highest negative impacts on GDP. Logistically well-connected, diverse, and strong services sectors all lead developed economies to experience the least impacts from higher transport costs.

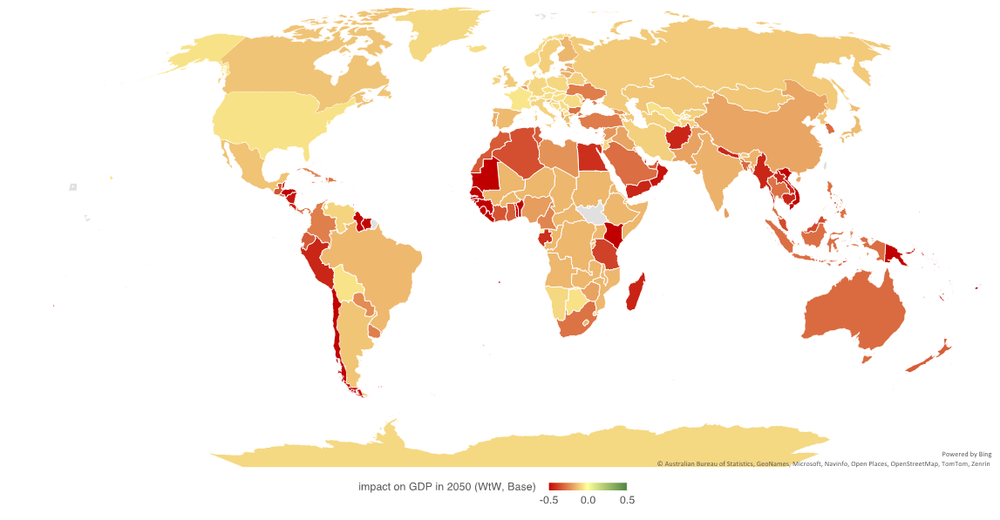

A fuel-standard-led transition (internally trading the costs between ship operators) has no obvious potential to integrate mitigation of the regressive impacts on trade and development into its effects. As a result, under this policy scenario many African economies, some central and southern American and Asian economies (especially Asian LDCs), and most of the SIDS see GDP impacts of around 0.5% reduction relative to a “business-as-usual” scenario (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Impact on GDP in 2050 of Fuel-Standard-Led Transition

Source: Produced from UNCTAD Impact on States data, scenario 24.

Note:

Fuel-standard-led transition particularly supported by Angola,

Argentina, Brazil, China, Ecuador, Norway, South Africa, United Arab

Emirates, and Uruguay.

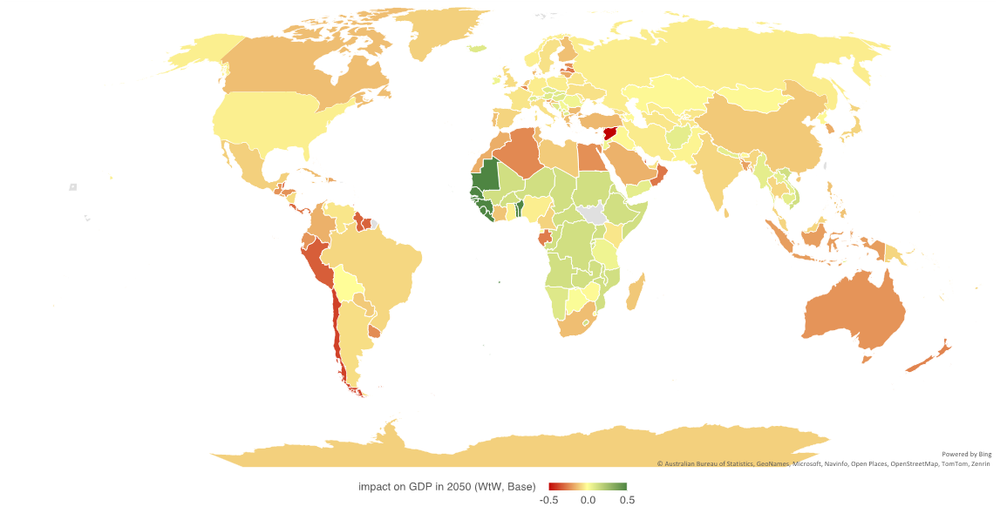

In the levy-led policy scenario, because only a portion of revenues are needed for energy transition, there is still a sizable share of revenues available for redistribution to economies (a $100/tCO2e GHG price would generate around $100bn per annum from international shipping). The modelling was too high-level to allocate revenue to specific sectors so only considers revenue distribution as an injection of general support (subsidy for consumption of the average household). The distribution of revenues between countries was done by prioritizing revenues to those countries experiencing the strongest economic impacts (before revenues distribution), and in consideration of their population size—e.g. greater magnitudes of revenue were given to countries with larger populations and higher negative GDP impacts.

Because many of the countries experiencing strong negative impacts are also the smallest economies, even modest revenues from a GHG price on shipping emissions can go a very long way. Not only are all developing countries less impacted in this scenario, including the larger economies that generally experience lower economic impacts under the fuel-standard led transition (e.g. China, Brazil, India, Argentina, South Africa), but the LDCs and the SIDS in Africa and Asia, particularly, switch from increasing inequity to (in some cases) similar or even lower inequity relative to other countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact on GDP in 2050 of Levy-Led Transition

Source: Produced from UNCTAD Impact on States data, scenario

26—revenue distribution to all developing countries, SIDS, and LDCs.

Note: Levy-led transition particularly supported by Belize, Fiji,

Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu, Tonga, Solomon

Islands, and Vanuatu.

The UNCTAD study also looks beyond GDP to trade volume and consumer price effects, and looks at interim points in time (2030, 2040), as well as the long run. Generally, the effects on volumes (both imports and exports) are more significant in developing countries and especially LDCs, reaching a maximum reduction in the LDC aggregate of around 0.5% in volumes by 2050. The effects of revenue disbursement can create larger changes in trade volumes, especially where the revenue use stimulates trade-related consumption. Consumer prices are estimated to rise as a result of all policy scenarios, varying between an increase of 0.21 to 0.044% in 2030 and between 0.38 and 0.2% by 2050 (depending on the country grouping).

While the results indicate that revenue distribution to countries with higher negative impacts has the potential to counter some of these effects, one risk associated with trade and consumer price impacts that received particular attention was related to food security, and was particularly raised by African economies. It was agreed for there to be further investigation, and the findings related to this risk will likely be important to further rounds of negotiation on how best to find a balance fair to all countries in the finalization of the policy design, including how to satisfy the IMO’s stated commitment to “contribute to a just and equitable transition” and to “address disproportionate negative impacts.

Concluding Remarks

The evidence is clear, and although many questions can and should be asked of the modelling assumptions and method, it is not a novel or surprising finding that redistribution and support to lower income economies (or households) is both fairer and ultimately benefits all. But the equity test of this multilateral organization is whether or not the IMO can grapple with policymaking to incentivize not just an energy transition, but an equitable energy transition.

The success or failure of that outcome depends on the extent to which the IMO sees its future as a continuation of its siloed past. Is it a specialist technical rule-making organization with a focus exclusively on “the ship”? Or is it an integrated component in a network of UN agencies with common objectives to tackle societies fundamental challenges—SDGs, climate crisis, finance and debt, etc.?

Given the IMO is ultimately at the service of the same member state constituencies as all the other UN agencies, this is also predominantly a question of those member states. They also have the opportunity to increase coherence in the positions taken across UN agencies with overlapping agendas. Such coherence between the IMO, climate, and climate finance threads across multilateral organizations rapidly needs to come together. This is because if the IMO does go ahead with a universal GHG price, the efficient and effective disbursement of revenue rapidly becomes the critical point of success or failure as to whether the actual GDP consequences are in line with UNCTAD’s modelling or not.

----------

Tristan Smith is Professor at UCL Energy Institute.

-----

Synergies by TESS is a blog dedicated to promoting inclusive policy dialogue at the intersection of trade, environment, and sustainable development, drawing on perspectives from a range of experts from around the globe. The editor is Fabrice Lehmann.

Disclaimer

Any views and opinions expressed on Synergies are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

License

All of the content on Synergies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

license. This means you are welcome to adapt, copy, and share it on your

platforms with attribution to the source and author(s), but not for

commercial purposes. You must also share it under the same CC BY-NC-SA

4.0 license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here or if you have any other question related to Synergies, send an email to fabrice.lehmann@graduateinstitute.ch.