There is an urgent need for innovative solutions to address the global plastic pollution crisis. A promising approach is to utilize nature’s renewable resources, including marine-based resources, to develop and scale up non-plastic substitutes and plastic alternatives. Trade can play a key role in this transition.

An Erupting Global Crisis

The 20th century was marked by some regrettable technological and industrial choices, such as the use of leaded gasoline or DDT as an agricultural pesticide until bans and controls were later introduced. What was once perceived as remarkable solutions to economic growth and development became societal calamities taking a huge toll on human health and the environment. In recent years, another wonder product, plastics, whose production has grown exponentially, has become the engine of an alarming global crisis; choking oceans, littering beaches, entering food chains, and invading our bodies.

It is estimated that every day the equivalent of 2,000 garbage trucks full of plastics are dumped into the planet’s oceans, rivers, and lakes, disrupting ecosystems and threatening human health. The projections are also bleak. Without action, stocks of accumulated plastics in the aquatic environment will more than triple from 140 to 493 million tonnes between 2019 and 2060. While bans on single-use plastics or waste management regulations are a start to addressing the plastic pollution crisis, there is an impelling need for scalable solutions that shake the plastics economy to its foundations and revolutionize material flows influencing production and consumption.

Natural Substitutes as Part of the Solution

To turn off the tap of plastic pollution, we need to replace plastics with alternative materials that perform the same functions with lower environmental impact. While doing so, we need to open up new production possibilities and markets that—unlike plastics—contribute to regenerating nature. This is not an easy task, but it is possible.

Non-plastic substitutes and plastic alternatives offer the potential to align environmental goals with socio-economic objectives, especially in developing countries (particularly for substitutes or alternatives produced from agri-residues and other sources that are not intensive in land use).* For these countries, producing such materials can nurture indigenous capacities, create jobs, and boost exports, thereby capitalizing on their natural resources and waste. This is the case of bagasse, for example, a by-product of sugar production which is widely produced in developing countries and is increasingly seen as a viable substitute for plastics in packaging and everyday products such as cutlery and bags.

Ranging from algae-based polymers for bioplastics to marine compounds used as fillers in glass and ceramics, marine-based substitutes and alternatives to plastics are of natural origin and extracted from abundant marine resources. For these reasons, they offer unique advantages over terrestrial alternatives.** For example, seaweed production is not intensive in freshwater or land use, and does not require pesticides or fertilizers. It generates a lower carbon footprint than natural fibres from agriculture, while also providing economic opportunities for coastal communities.

Early Signs of a Market Movement

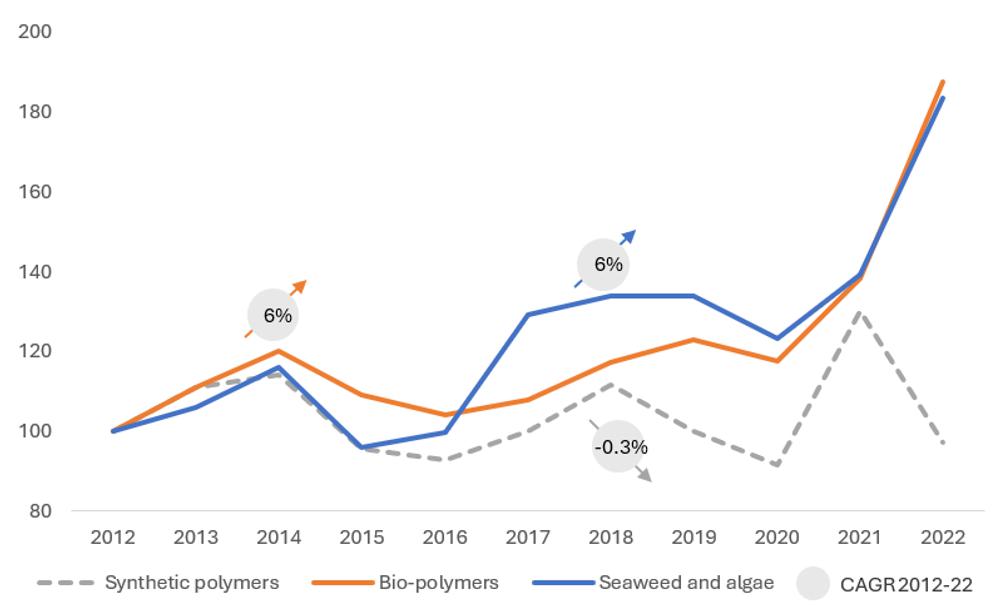

A closer look at the data suggests that a shift in material markets towards non-plastic substitutes and alternatives may already be underway. The global market for marine-based substitutes and alternatives, for example, is already worth $10.8 billion and is expanding, driven by the rapid growth of certain segments. For instance, global exports of marine biopolymers, including agar-agar and alginates, grew at an average annual rate of 6% between 2012 and 2022. This is six times faster than their synthetic equivalents (Figure 1). Developing countries play an increasingly important role in these shifts, with some of the main trading hubs located in the developing world. Indonesia, for example, was the world´s largest exporter of seaweed in 2022.

Figure 1. Global Exports of Marine Biopolymers and Seaweed vs. Synthetic Polymers (Base Year: 2012 = 100)

Source: UNCTAD. (2025, forthcoming). Leaving the shore: Marine-based substitutes and alternatives to plastics.

As these figures show, trade can enable the transition to sustainable plastic alternatives. By opening up new markets, it allows producers to scale up their operations. It also facilitates the shift to sustainable materials by making them more accessible in regions where they are scarce. For example, by importing seaweed-based packaging, countries that lack natural resources can reduce their reliance on predominantly synthetic single-use plastics. This simultaneously curbs fossil fuel use in production and pollution from consumption, leading to significant environmental benefits.

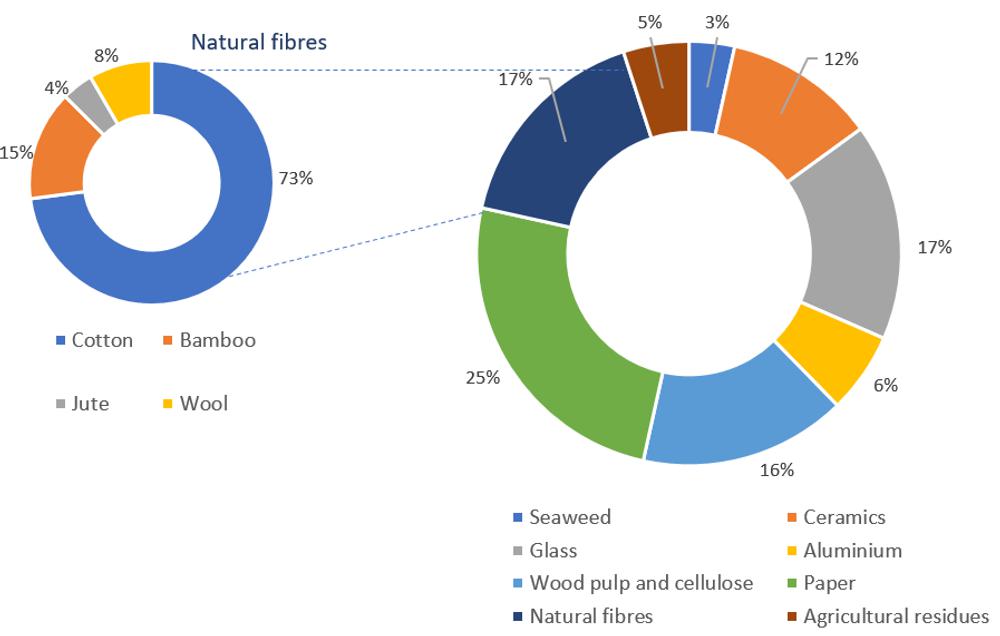

The rising interest in sustainable materials is reflected in the increasing number of measures regulating and supporting their trade. UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has examined environmental measures notified by World Trade Organization (WTO) members, revealing that measures targeting non-plastic substitutes increased by an average 13% per year over the period 2009–2021; twice as fast as all environmental measures. With paper, glass, and natural fibres being the most targeted materials, the notified measures include both technical regulations and support instruments, ranging from import bans on non-plastic substitutes to direct cash transfers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Environmental Measures Targeting Non-Plastic Substitutes Notified to the WTO, by Commodity/Material (2009–21)

Source: UNCTAD. (2024). Beyond plastics: A review of trade-related policy measures on non-plastic substitutes.

Hurdles Along the Way

There are challenges, however, in scaling up non-plastic substitutes, particularly in developing countries where producers can face economic and regulatory hurdles related to market size and capacity constraints. For example, the development of algae-based plastic alternatives can be held back by technologies that are expensive to acquire and require specialized skills. Low production volumes and high costs can also limit the achievement of economies of scale, making these alternatives too expensive to compete with conventional plastics. Consequently, bio-based plastics are sold at a premium, with average prices two to three times higher than for conventional plastics.

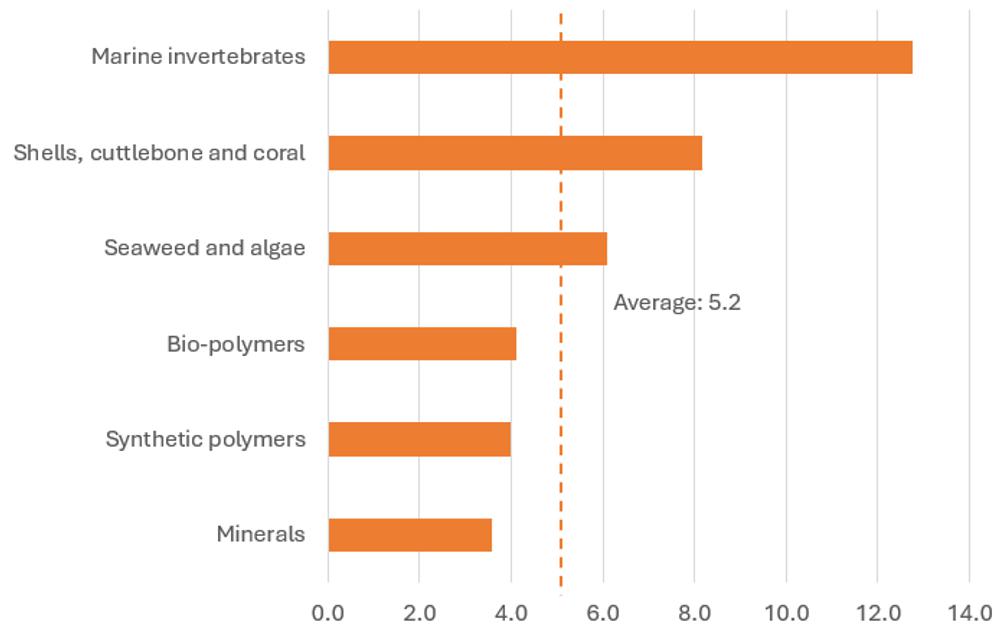

Import tariffs and regulations also constrain access to global markets. Although the average most-favoured-nation (MFN) tariffs applied to marine bio-polymers are only slightly higher than those applied to synthetic polymers, the raw materials used to produce many of these alternatives, such as mollusk shells and jellyfish, are subject to tariffs that are up to three times higher (Figure 3). While this creates opportunities for value-added sectors in coastal developing countries, it can restrict access to critical raw materials and strain supply chains.

Figure 3. Average MFN Tariffs Applied to Marine-Based Substitutes and Alternatives vs. Synthetic Polymers Globally, by Material Category

Source: UNCTAD. (2025, forthcoming). Leaving the shore: Marine-based substitutes and alternatives to plastics.

The complexity of regulations is another barrier. For example, many countries still categorize and cover seaweed-based products under food regulations, subjecting them to non-tariff measures that are unnecessary for non-food applications such as packaging. Intended to safeguard human health, sanitary and phytosanitary measures often require certifications that can impose significant financial and technical burdens on exporting firms. Combined with limited harmonization, such standards and measures disproportionately impact small firms, especially in developing countries that lack the financial and technical resources to comply with these measures.

The Way Forward

To help overcome these hurdles, governments, international organizations, businesses, civil society organizations, and academia need to work together to build a supportive ecosystem for sustainable trade in non-plastic substitutes and plastic alternatives. Here, policy coherence and coordination are key, hence the importance of multilateral frameworks, including those arising from the UN’s International Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop a global plastics treaty, as well as regional efforts like the East African Community bill on prohibiting single-use plastics. Currently in draft form, the bill aims to establish a harmonized regional approach to tackling plastic pollution by banning non-essential plastic items.

Governments, international organizations, businesses, civil society organizations, and academia need to collaborate to build a supportive ecosystem for sustainable trade in non-plastic substitutes and plastic alternatives.

Governments should create an enabling environment through supportive policies, market incentives, and infrastructure investments that address key market failures. This includes the harmonization of standards and refined product classifications based on the World Custom Organization’s Harmonized System, widely used in international trade. With appropriate support and incentives, businesses can drive innovation and bring substitutes and alternatives to market, from raw material extraction to retail. Academia can advance scientific knowledge and provide expert advice to policymakers and industry. Civil society organizations can shed light on the various dimensions of plastic pollution and advocate for policy and behavioural change.

Policy dialogue that connects multilateral fora with local stakeholders is essential to sustain change and make policies effective. Decisions made in international fora often have direct consequences for local producers, who may not be fully aware of or prepared for these regulatory shifts. Bridging the gap between international decision-making hubs and local supply chain actors can foster a better flow of information, enabling producers in developing countries to participate in and benefit from these policy changes rather than being adversely affected.

These principles are well reflected in the ongoing negotiations for a global plastics treaty—a promising example of how multilateral processes can include substitutes as part of a comprehensive global strategy to combat plastic pollution. With reference to “fostering research, innovation, development and use of sustainable alternatives and non-plastic substitutes,” the INC chair´s non-paper proposed as a basis for negotiations at the INC´s fifth session in Busan, Republic of Korea, illustrates how the INC can help level the playing field in the global materials market. The INC negotiations also highlight the importance of inclusivity and diversity in policymaking by giving a voice to stakeholders from a broad range of countries and sectors.

In conclusion, the fight against plastic pollution demands well-functioning markets, global cooperation, and inclusive policy frameworks. By promoting sustainable alternatives and substitutes to plastics through trade, plastic pollution can be addressed beyond the use of control measures in ways that foster socio-economic benefits and market innovation.

-----

* Non-plastic substitutes are natural materials of mineral, plant, animal, marine, or forestry origin that have properties similar to those of fossil fuel-based plastics. They are typically biodegradable/compostable or erodible in nature and suitable for reuse, recycling, or disposal. Plastic alternatives are bioplastics derived from biological sources such as biomass ("bio-based plastics") or have biodegradable properties ("biodegradable plastics").

** Polymers are large molecules formed by linking numerous smaller molecules, called monomers. These monomers act as repeating units, creating a long chain-like structure. The specific properties of a polymer (strength, flexibility, etc.) allows them to be the fundamental building blocks of plastics. By varying the monomer and chain structure, a vast array of plastics are produced with a wide range of characteristics and applications.

----------

Lorenzo Formenti is a consultant for UN Trade and Development.

Henrique Pacini is Programme Lead, Sustainable Manufacturing and Environmental Pollution (SMEP) Programme.

This article reflects solely the personal views of the authors and not those of their institutions. It is based on research conducted by the authors, including Plastic Pollution: The pressing case for natural and environmentally friendly substitutes to plastics, An ocean of opportunities: The potential of seaweed to advance food, environmental and gender dimensions of the SDGs, Beyond Plastics: A review of trade-related policy measures on non-plastic substitutes, and Leaving the shore: Marine-based substitutes and alternatives to plastics (UNCTAD, 2025 forthcoming).

-----

Synergies by TESS is a blog dedicated to promoting inclusive policy dialogue at the intersection of trade, environment, and sustainable development, drawing on perspectives from a range of experts from around the globe. The editor is Fabrice Lehmann.

Disclaimer

Any views and opinions expressed on Synergies are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

License

All of the content on Synergies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

license. This means you are welcome to adapt, copy, and share it on your

platforms with attribution to the source and author(s), but not for

commercial purposes. You must also share it under the same CC BY-NC-SA

4.0 license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here or if you have any other question related to Synergies, send an email to fabrice.lehmann@graduateinstitute.ch.