From production methods, supply chain analysis, the assessment of greenhouse gas emissions, and labelling of goods to advertising of services, standards play a central role in ensuring that environmentally sound trade is accessible, supported, and trusted. While economic diplomacy in the pursuit of such trade has focused on liberalization or (to a lesser degree) regulation, by engaging actively in the standards space, governments can support meaningful climate and environmental outcomes.

This article is part of a Synergies series on climate and trade curated by TESS titled Addressing the Climate Crisis and Supporting Climate-Resilient Development: Where Can the Trading System Contribute? Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

-----

The pursuit of environmentally sound trade has become a priority for governments and core part of the economic diplomacy of many, pursuing their policy objectives through multiple institutions of trade and economic coordination. World Trade Organization (WTO) members have continued discussions at the Committee on Trade and Environment (CTE) and through the Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions (TESSD) to facilitate “greener” trade (for example, mapping hydrogen value chains). At the same time, many have pursued environmental goods and services (EGS) liberalization through free trade agreements (FTAs) like the New Zealand–United Kingdom FTA with its prioritization of EGS, or other non-WTO plurilateral efforts such as the recently concluded Agreement on Climate Change, Trade, and Sustainability (ACCTS).

Others still have pursued active unilateral liberalization, such as the UK’s post-EU global tariff, which includes the removal of tariffs on over 100 environmental goods. At the same time, some WTO members have increased the rigour of their supply chain due diligence requirements (for example on forest-risk commodities) or their assessment of the carbon liabilities of goods through internal carbon taxes and, in some cases (such as the EU and UK), border carbon adjustments.

As businesses and policymakers seek to fashion more environmentally sound supply chains, the means to determine what is truly green and what is greenwashing becomes harder. From production methods, supply chain analysis, the assessment of greenhouse gas emissions, and labelling of goods to advertising of services, standards play a central role in ensuring that environmentally sound trade is accessible, supported, and trusted. While economic diplomacy in this field has focused on liberalization or (to a lesser degree) regulation, without standards meaningful environmental outcomes will be inevitably limited.

The Role of Standards in Environmentally Sound Trade

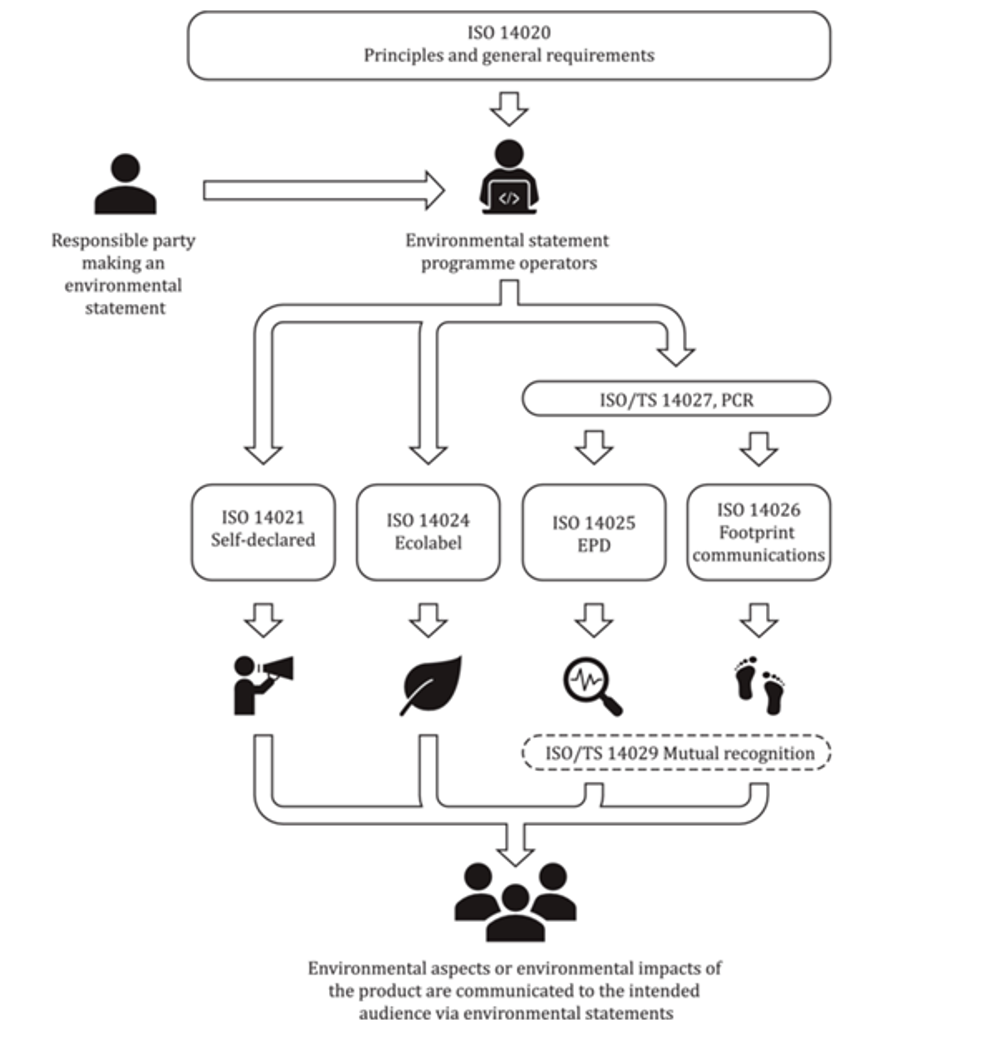

Underpinning global trade, hidden from plain sight, is the critically important role of standards—in essence documents that set out best practice. Standards may relate to goods, services, or organizations. For example, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has developed a suite of standards to identify best practice for the development of different types of environmental claims that are made— whether by the producer themselves (self-declared), in accordance with set criteria and verified by a third-party (ecolabels), or quantifying environmental information of the product (environmental product declarations – EPDs). Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the ISO 14020 family of standards, which provide principles and requirements for communicating environmental aspects and potential environmental impacts of products.

Figure 1. Structure of the ISO 14020 Family of Standards

Source: ISO 14020:2022 (3rd ed).

Standards cover both the general (as above) but also the specific: they include guidance on what species of fish can be called sardines when canned, the maximum residue limits of pesticides on specific crops, a series of standardized paper sizes including the near-ubiquitous A4, or how to calculate what your businesses carbon emissions are and how to set up and run environmental management systems. Some standards are developed through formally recognized national standards bodies or regional or international standards bodies. Others are developed by groups of private stakeholders—sometimes businesses (e.g. commercial standards like 5G) or nongovernmental organizations (e.g. the Forest Stewardship Council – FSC).

Whether public or private, standards though useful can be contentious. Public processes of standardization are historically slow, exacerbated by the consensus based decision-making process of standardization. And while standards bodies aim to include multiple stakeholders, they are often dominated by economic actors (logically as they are usually the principal consumer of the standard). This additionally leads to criticisms that they are “low-ambition” when it comes to non-economic interests such as the climate or public health. Meanwhile, private standards, especially voluntary sustainability standards, can be of high quality and well-respected, yet there are many of them and limited mechanisms to govern their creation or criteria (the EU’s Green Claims Directive is a notable exception). As such, voluntary sustainability standards are often criticized for being complicit in “greenwashing” or presenting unreasonably restrictive requirements for less well-resourced producers and thus reducing development opportunities for some of the world’s poorest.

Government’s role in the standards space is limited, but not absent. The intergovernmental trade regime, most notably the WTO, encourages the use of formal (public) standards through a set of incentives: legal obligations to use internationally agreed standards as the basis of mandatory product requirements (Art. 2.4 of the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade – TBT Agreement) and a related presumption that government measures are no more trade restrictive than necessary to meet their legitimate objective (Art. 2.5 of the TBT Agreement). However, while this encourages engagement with the international standards infrastructure, it only relates to public international standards. The increase in private standards in the environmental space, especially ecolabels, has raised concerns that trade rules are silent on private measures that may nonetheless impede producers’ access to export markets (an issue raised formally at the WTO in the context of agrifood private standards for over twenty years).

Recently, governments have moved to bridge this gap: FTAs increasingly include provisions to cooperate on the development and application of ecolabels (e.g. UK – New Zealand FTA Art. 22.17.3), and the ACCTS includes Guidelines for Voluntary Ecolabelling Programmes (Article 5.4) that set out exactly the features to which all bodies developing ecolabels should aspire—ensuring that the ecolabels are accurate, do not mislead, are based on evidence, are no more burdensome to comply with for business than necessary, non-discriminatory, evidence-based, and so on.

There are limitations however. As noted, these ecolabels are rarely developed by governments or governmental bodies (including national standards bodies). As such, governments can work to encourage the improvement of ecolabelling within their territories but that is as far as they can go. And while the guidelines note that ecolabels “should be aligned with relevant international standards, recommendations or guidelines, support harmonization of best practices and avoid duplication with international standards and international instruments” they are not required to do so.

Improving Access to Quality Standards

What could be done? An attempt could be made to insist on standards being developed within the traditional public standardization system (national, regional, and international standards bodies). However, this is not feasible given the lack of responsiveness of many of these bodies, their structural preference for (often) catering to the demands of economic actors without factoring in negative externalities, or their decision-making procedures which disincentivize civil society to sign up to “low-quality” standards. And further, the ship has sailed in many areas of environmental policy: in forestry management, for example, for decades the dominant standards are voluntary sustainability standards (FSC and PEFC). There is little appetite to develop new “public” international standards to replace them as, for their imperfections, they are largely well-regarded.

This is not a counsel of despair, however. The underlying standards infrastructure must be strong, accessible, and encourage high ambition in relation to climate and environmental standards while recognizing and responding to interests of all relevant economy actors—especially developing country producers. Governments can play a key role in supporting this process by leveraging their convening power to facilitate the development and adoption of high quality standards. Rather than agreeing to formal new trade instruments, this is instead a prioritization of the practice of economic diplomacy to drive the development and accessibility of improved standards.

We have existing examples to draw on: confronted by the need for fast and inclusive instruments to support climate policies, Our 2050 World (a collaboration between the ISO, Race to Zero initiative, and the UNFCCC Innovation Hub, convening over 1200 organizations and individuals from over 100 countries) led the development of the ISO Net Zero Guidelines providing common language and shared definitions around net zero.*

One of the reasons why the ISO Net Zero Guidelines have had considerable reach is because they are freely available, unlike most standards which must be purchased. To shift this dynamic, the UK national standards body, the British Standards Institution (BSI), recently developed and published a freely accessible Code of Practice for net zero transition plans for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (BSI Flex 3030 v2.0:2024-12). Much like the ISO Net Zero Guidelines, while not formally a standard against which one could test, this code of practice nonetheless provides a valuable resource for SMEs to develop their net zero plans. It references both public (BSI and ISO) standards as well as the key private standards (most notably the Greenhouse Gas Protocol).

Another example of the influence of collaborative (public and private) standards instruments that can be made freely available includes the UK Forestry Standard, which is a single accessible document setting out the different regulatory and legal requirements for forestry managers in the UK’s different jurisdictions as well as best practice targets (for example on biodiversity). It is designed to overlap with requirements of key private voluntary standards schemes in forestry management so that users can have confidence in their management practices and ability to certify for both.

The Kenya Bureau of Standards has also developed a standard (KS 1758-2:2016) setting out requirements for legal compliance, responsible procurement of inputs, safe production, handling, and marketing of fresh fruits, vegetables, herbs, and spices. Currently being revised, KS1758 reflects commonly used GLOBALG.A.P standards, which, while a private voluntary standard scheme, is highly influential, with many retailers requiring compliance with GLOBALG.A.P as a condition of purchase.

Placing Standards at the Heart of Economic Diplomacy

What lessons can governments take from these examples? There are formal institutions of trade policy where governments can support the development of collaborative projects, much like the ACCTS guidelines. They could seek to adopt these guidelines or confirm agreed positions on key standards, guidelines, or codes of practice, through their FTA committees or indeed at the WTO as a Decision (mostly likely at the CTE or, ideally, the TBT Committee). This would improve coherence within the trade landscape, aligning the standards and public governance structures on these issues. It would also provide an additional space in which to discuss the implementation, monitoring, and improvement of the substance of instruments, such as the ACCTS guidelines, and share best practices.

Most importantly, by mainstreaming standards within the economic diplomacy of governments for environmentally sound trade, they could pursue a multi-institutional strategy to tackle the three hurdles for less-resourced businesses: access to standards, certification costs, and access to investment.

To improve access to standards, which for smaller economic actors entail significant costs, governments could work in multiple fora—for example, a G20 statement confirming the creation of an Inclusive Standards Group (convened by governments but comprised of national standards bodies, key voluntary standards schemes, civil society, and businesses) to develop new accessible standards would be valuable. Commonly agreed and freely accessible standards, tailored to SMEs (in the North and South), along the model of the ISO Net Zero Guidelines or BSI Flex 3030, would provide a helpful starting point and support for businesses that want clear and accessible standards to meet—and benefit from—new climate-related trade policy instruments. By removing the entry barrier of cost, this would support more consistent improved practice (whether in production, monitoring, reporting, or elsewhere) and align business practices with the requirements of different certification schemes.

Where standards focused on environmentally sound trade are made freely available, certification will still be required for many of these standards. Certification is a potentially costly process that disincentivizes SMEs from taking part in global value chains. At the WTO, members could support an expansion of the Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF) to include climate-supportive (TBT) standards, which would allow key stakeholders in the international standards space to engage through the facility. Meanwhile, at the unilateral and regional levels, governments could use their development projects, aid for trade schemes, and other programmatic spending to support investment in certification, helping to reduce these barriers.

Finally, to support investment, and help mitigate the increasing risks and costs presented by unilateral trade-related measures linked to climate or the environment (such as border carbon adjustments or the EU Deforestation Regulation), governments could further strengthen the effect and impact of standards by explicitly referencing them in new regulatory requirements—for example by presuming compliance with elements of due diligence legislation on deforestation should businesses meet the requirements of these standards.

By reducing costs for businesses—without lowering ambition for climate targets—open, accessible, and development-friendly standards could play an important role. While it would not be for governments to develop these standards, through the practice of economic diplomacy they could improve their reach and impact, driving a more inclusive green global economy.

* On the ISO Net Zero Guideline: see Jones, E., & Messenger, G. (2023). TaPP Insights: Net Zero and UK Trade (2023); and on using FTAs to support their uptake, see Messenger, G. (2025). Free Trade Agreements as Sites of Economic Diplomacy: Agreeing Common Standards for Sustainable Development.

----------

Greg Messenger is Professor of Trade Law and Policy, University of Bristol Law School..

-----

Synergies by TESS is a blog dedicated to promoting inclusive policy dialogue at the intersection of trade, environment, and sustainable development, drawing on perspectives from a range of experts from around the globe. The editor is Fabrice Lehmann.

Disclaimer

Any views and opinions expressed on Synergies are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

License

All of the content on Synergies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

license. This means you are welcome to adapt, copy, and share it on your

platforms with attribution to the source and author(s), but not for

commercial purposes. You must also share it under the same CC BY-NC-SA

4.0 license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here or if you have any other question related to Synergies, send an email to fabrice.lehmann@graduateinstitute.ch.