Sustainable trade presents a vital pathway for aligning international trade with climate goals and enhancing resilience in developing countries. However, financing gaps hinder scaling up of green trade. This article advocates for "greening" aid for trade by aligning it with climate objectives and increasing climate finance commitments. Through strengthening multilateral coordination, closing climate finance gaps, and prioritizing sustainable trade, the global community can ensure that trade becomes a driving force for sustainability, just transitions, and climate resilience.

This article is part of a Synergies series on climate and trade curated by TESS titled Addressing the Climate Crisis and Supporting Climate-Resilient Development: Where Can the Trading System Contribute? Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

-----

Trade, including transport and logistics, is a significant contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet trade can also help accelerate the shift towards a green economy and the net zero ambition by easing access to environmental goods and clean technologies, creating markets for green products, and supporting sustainable production and consumption (for example circular economy practices). Moreover, trade measures such as border carbon adjustments can reduce carbon leakage while trade-induced product and market diversification can enhance the climate resilience of supply chains and foster sustainable agriculture. Evidence suggests that most developing countries have already integrated trade in their sustainable development strategies, which signals a global movement towards more sustainable or greener trade.

However, as with supporting climate action at the global level, encouraging and scaling up green trade is in dire need of financing. This article surveys recent efforts at mobilizing climate finance for this purpose, highlighting current gaps and discussing options for plugging them. A key area of attention is the Aid for Trade (AfT) initiative, which, we argue, can be modified slightly to emphasize the complementarity between trade and climate finance. We call for AfT to refocus on the sustainable trade agenda—or “greening” the AfT initiative.

What is Sustainable Trade?

Sustainable trade can be defined as trade that minimizes environmental harm and preserves environmental resources, promotes social welfare, and supports long-term economic resilience. It emphasizes green trade (e.g. trade in low-carbon goods and clean technologies), fair trade (e.g. ethical supply chains that safeguard labour rights), and circular trade (e.g. trade in recycled materials and sustainably sourced products).

Practical examples of sustainable trade abound. They include exports and imports of environmental goods (e.g. solar panels and wind turbines), trade in certified products (e.g. Fairtrade coffee), and carbon-neutral supply chains (e.g. Namibia’s green hydrogen exports and the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – CBAM).

Sustainable trade can support a just transition, for example by creating green jobs in renewable energy and eco-industries, reducing inequality through fair wages and ethical supply chains, and enabling climate resilience by financing climate change adaptation in vulnerable economies.

Persistent Climate Finance Gaps

Developing countries require substantial climate finance—some $2.4 trillion annually up to 2030—to meet mitigation and adaptation goals. According to UNEP, the cost of adaptation alone is about $240 billion per year. However, despite a steady increase since 2015, climate finance flows have fallen short of the annual target of $100 billion agreed at the Paris Climate Conference (COP15). Moreover, less than 40% of climate finance has been allocated to adaptation (e.g. early warning systems, flood defenses, drought-resistant crops, etc.), which remains an urgent priority for developing countries that have contributed little to climate change but are most exposed to its disastrous consequences.

The climate finance gap may widen as the United States—which has barely provided 5% of its fair share (based on income, population size, and cumulative emissions since 1990) in recent years and is overwhelmingly responsible for the persistent gap—scales back aid and withdraws from the Paris Agreement. Few other developed countries have provided their fair share of climate finance over the past 10 years; only four countries (Norway, Sweden, France, and Japan) are expected to do so in 2025.

Bilateral climate finance is not only limited; lack of coordination among donors has resulted in such funds being fragmented and concentrated in a few specific sectors (notably energy and transport) and in mitigation projects. While there is an array of multilateral climate funds, complex application processes have hindered access, challenging developing countries that are notoriously deficient in administrative capacity.

For these reasons, recent discussions on climate financing have argued that the onus to address climate change and its impacts should rest with the developing countries themselves. Proponents of this view emphasize the potential of innovative financing options such as green bonds or ESG-linked loans, public-private partnerships, blended finance initiatives, and debt-for-climate swaps. However, many debt-strapped developing countries lack the creditworthiness and the fiscal space to raise green finance or make green investments. Moreover, it is unfair to ask developing countries to pay for a crisis that they are barely responsible for.

Financing the Transition to Sustainable Trade in Developing Countries

Given these constraints, external public financing—preferably aid—will remain critical to supporting the transition to sustainable trade in developing countries.

Climate-Related Official Development Assistance

One approach is to lobby for scaled-up climate-related official development assistance (ODA) from the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors.

Since 2002, the OECD has reported ODA statistics by climate change objective using the co-called Rio markers, which identify the extent to which an aid activity has specifically stated any such objective (the four Rio markers are biodiversity, desertification, climate change mitigation, and climate change adaptation.) Bilateral climate-related ODA (i.e. aid that explicitly targets climate change) has increased substantially since 2002, reaching a peak of $93.4 billion in 2022, but dropping slightly the following year (see Figure 1). Since these commitments fall short of the $100 billion target set at COP15, one can only hope that the decline in 2023 is temporary.

As shown in Figure 1, adaptation finance was virtually inexistent prior to 2010. Even today, ODA for climate change adaptation accounts for a comparatively modest share of climate-related aid commitments, reaching about 40% of the total in recent years. Moreover, the bulk of these commitments takes the form of loans, albeit concessional, rather than grants per se.

Figure 1. Climate-Related ODA By Policy Objective, 2002–2023 ($ billion)

On a positive note, bilateral climate-related ODA represents a rising share of total bilateral aid, reaching 32.9% in 2021-22. Hopefully, this is new and additional funding rather than a mere relabelling of aid. Furthermore, DAC bilateral aid flows are just a portion—albeit an important one—of climate-related finance available to developing countries. The latter includes “other official flows” (non-concessional finance) from DAC members, bilateral flows from non-DAC providers, and multilateral development finance, including from multilateral development banks and UN agencies.

The fact remains, however, that much of climate finance is targeted at mitigation activities. Yet, the empirical evidence so far fails to support the view that mitigation aid is associated with lower emissions in recipient countries. This could be due to mitigation finance being misnamed or misused. Be what it may, the lack of effectiveness of mitigation finance in achieving climate change mitigation in recipient countries suggests that the costs to developing countries of diverting ODA to mitigation objectives—especially if it is away from adaptation—could be significant.

Aid for Trade

The Aid for Trade initiative was designed to help developing countries integrate into the global trading system by strengthening their trade policies and regulations (e.g. customs modernization and trade facilitation), building trade-related infrastructure (e.g. ports, roads, and digital connectivity), and enhancing productive capacity (e.g. in sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing). Since the initiative’s launch in 2006, AfT disbursements have increased steadily (except for a slight dip in 2021 following the COVID-19 pandemic) to reach a peak of $51.1 billion in 2022. Cumulative AfT disbursements amounted to $648 billion, representing nearly 20% of total ODA disbursements. Historically, the quasi-totality of AfT has flowed into economic infrastructure (notably energy generation and transport) and productive capacity building (in particular agriculture, forestry, and fishing). In 2022, these two categories accounted respectively for 54.6% and 43.6% of disbursements.

Complementarity Between Aid for Trade and Climate Finance

While AfT has traditionally focused on economic development through trade, recent discourse has emphasized its potential to address climate change by financing sustainable trade initiatives.

The link between AfT and climate finance was first explored in the academic literature in a paper we authored in 2010, in which we argued that many climate-related projects (most notably in sectors like agriculture and energy) have clear trade-related impacts. For example, the uptake of climate-smart agriculture can boost agricultural output and exports. Similarly, mitigation projects like renewable energy development can enhance energy security and support industrial activity such as export-oriented manufacturing.

Thus, AfT can be mapped to climate-related projects. The rehabilitation of weather-battered infrastructure or the protection of coastal zones from sea level rise, for instance, are as much AfT projects in the “economic infrastructure” category as they are climate change adaptation projects. Under the category of “productive capacity building,” diversification into climate-resistant crops or away from climate-vulnerable sectors, such as traditional agriculture, are also adaptation projects.

The proposed mapping is more than an academic idea; it is already happening. For example, according to WTO surveys, 88% of developing countries had incorporated trade objectives in their sustainable development strategies in 2022, while 86% had integrated climate change objectives in their trade strategies.

Our 2010 paper suggested that developing countries can leverage the complementarity between AfT and climate change financing mechanisms to mobilize higher levels of climate finance. AfT can serve as co-financing for projects that integrate components of climate change adaptation (or mitigation) and trade competitiveness. Alternatively, AfT can be sought for climate change projects that can be mapped to an AfT category—e.g. dams (economic infrastructure) or soil rehabilitation (productive capacity building in the agriculture sector).

We proposed a roadmap for making AfT and climate finance mutually reinforcing. Such a strategy rested on optimizing the synergies between the two types of financing, improving their governance structures, and learning from their respective experiences. For example, climate projects are generally better coordinated and more fully owned than AfT projects, which, conversely, are better grounded in development and poverty reduction.

Climate-Related Aid for Trade

In 2024, the WTO and OECD explicitly noted for the first time that “Aid for Trade can […] play a role in supporting climate-related objectives.” In survey responses, 77% of recipients said that AfT can help finance climate action.

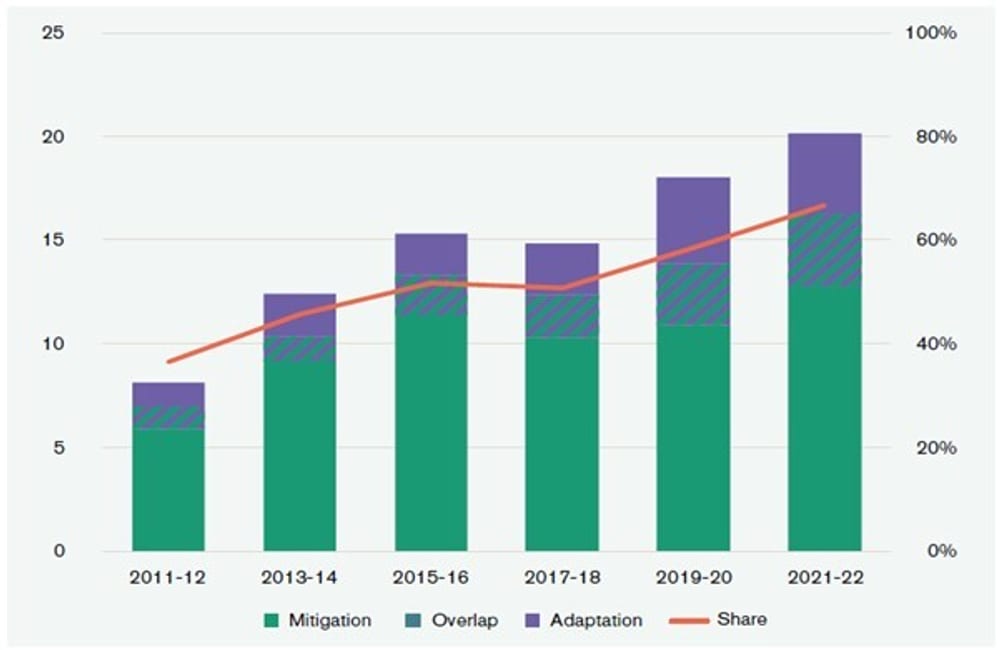

Concretizing the idea of mapping AfT to climate-related projects, the OECD CRS database reports “climate-related AfT” commitments since 2011. These commitments show a marked upward trend, increasing by more than 100% over the subsequent 11 years (Figure 2). In 2021-22, average climate-related AfT commitments of DAC donors represented 67% of their total AfT commitments, denoting that increasingly AfT is being targeted to climate-related adaptation and mitigation projects. Not surprisingly, the latter has dominated AfT commitments, with financing for green infrastructure, such as solar powered plants, accounting for the bulk of these flows. This dominance is partly attributed to the fact that mitigation projects are more appealing to investors since they “bring a more immediate and certain financial return than many adaptation initiatives”. Thus, there exists substantial room for AfT financing of adaptation projects and greener trade policies that enhance access to environmental goods and services.

Figure 2. Average Climate-Related AfT commitments, 2011–2022 ($ billion (left axis) and as a share of total AfT commitments (right axis))

Source: OECD (2024).

Green Trade Facilitation

The UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) and the Asian Development Bank are pioneering the concept of “green trade facilitation” as a means of making trade processes and supply chains less carbon-intensive and more sustainable. Green trade facilitation rests on four key pillars:

- Digitalizing trade procedures, which would make processes simpler, more transparent, and more environment-friendly (for example, paperless trade may lead to fewer trees being cut down and hence reduced emissions, waste, and water use).

- Facilitating trade in environmental goods, such as solar panels, clean energy technologies, and used and recycled goods and materials critical to the circular economy.

- Greening the transport of traded goods by supporting low-carbon modes of transportation, optimizing shipping routes, and shifting to alternative, cleaner modes such as rail.

- Facilitating compliance with climate-related non-tariff barriers, such as the EU’s CBAM and the EU Regulation on Deforestation.

Green trade facilitation calls for two things: (i) reprioritizing trade facilitation and scaling up the amount of aid flowing to this sector, and (ii) reorienting trade facilitation towards sustainable practices, including the four pillars described above.

There are challenges on both fronts. Trade facilitation is a subcategory of “trade policies and regulations,” which attracted just 2.5% of AfT disbursements between 2018–2022. Aid for trade facilitation is even thinner, amounting to $252 million in 2022—i.e. a mere 0.5% of total AfT disbursements. Green trade facilitation will thus remain a sheer concept unless donors are convinced that allocating more aid to trade facilitation can encourage its use in greener initiatives. More aid for this purpose should be additional and scalable, not just a diversion from other categories of AfT.

Looking Ahead

Sustainable trade presents a vital pathway for aligning international trade with climate goals, fostering inclusive growth, and enhancing resilience in developing countries. However, as highlighted, significant financing gaps persist, particularly in adaptation and green trade initiatives. While climate-related ODA and AfT have grown, they remain insufficient and imbalanced, with mitigation projects overshadowing adaptation needs.

The potential for AfT to support sustainable trade—through climate-resilient infrastructure, green trade facilitation, and low-carbon supply chains—remains underexploited. To advance a just transition and finance sustainable trade at the scale required, it is critical to:

- Refocus AfT on sustainable trade. Donors should explicitly integrate climate objectives into AfT, directing more funding towards adaptation-linked trade projects, such as climate-smart agriculture and green trade facilitation.

- Increase climate finance commitments. Developed nations must fulfill their $100 billion climate finance pledge, with greater emphasis on grants (rather than loans) and adaptation support for vulnerable economies.

- Leverage innovative financing. Blended finance, green bonds, and debt-for-climate swaps can supplement traditional aid, but these must be accessible to low-income countries through risk-sharing mechanisms.

- Strengthen multilateral coordination. Simplifying access to climate funds and improving donor coordination will ensure that financing reaches high-impact sectors like sustainable logistics and circular trade.

By greening AfT and closing climate finance gaps, the global community can ensure that trade becomes a driving force for sustainability rather than a source of emissions. Going forward, there is a need to concretize the synergies between sustainable trade and climate resilience. Further research in this area, with evidence from the ground, will help affirm the complementarities between AfT and climate finance. This could spur larger future AfT flows to the most climate-vulnerable developing countries. The time for action is now. Developing countries cannot afford further delays in securing the resources needed for a fair and just transition to sustainable and climate-resilient economies.

----------

Vinaye Ancharaz is Executive Director, National Productivity and Competitiveness Council, Mauritius.

Riad Sultan is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Mauritius.

-----

Synergies by TESS is a blog dedicated to promoting inclusive policy dialogue at the intersection of trade, environment, and sustainable development, drawing on perspectives from a range of experts from around the globe. The editor is Fabrice Lehmann.

Disclaimer

Any views and opinions expressed on Synergies are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of TESS or any of its partner organizations or funders.

License

All of the content on Synergies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

license. This means you are welcome to adapt, copy, and share it on your

platforms with attribution to the source and author(s), but not for

commercial purposes. You must also share it under the same CC BY-NC-SA

4.0 license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here or if you have any other question related to Synergies, send an email to fabrice.lehmann@graduateinstitute.ch.